By Jondi Gumz

With wildfires that broke out Aug. 8 in Maui causing an estimated $5.5 billion in damages, claiming 115 lives and 2,025 schoolchildren vanished, what lessons can we learn in Santa Cruz County?

On Aug. 24, the Hawaii Department of Education released a report: Of the 3,001 children in the Lahaina schools, there are 2,025 unaccounted for. This is the next generation!

The report said 538 re-enrolled in other public schools, and 438 enrolled in distance learning.

Remember, schools were closed on Aug. 8 due to hurricane winds, so children stayed home perhaps alone, perhaps with parents who skipped work.

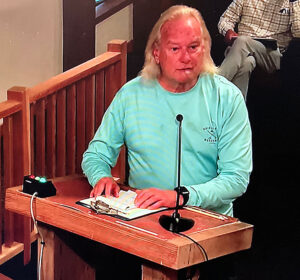

Dennis Norton, former Capitola city councilman, sees similarities.

The wildfire flattened Lahaina, a town of 13,000 on 2 square miles next to the ocean and a tourist hot spot.

Capitola is a city of 12,000 on 2 square miles, a tourist hot spot next to the ocean.

Warnings

How are people to be warned of a wildfire?

Sirens? Cell-phone texts?

In Maui, officials used social media, but those connections depend on Internet, and when power poles snap and power lines burn, you have no power.

Most phones rely on Internet, so that means no phones. No computers. No tablets. No cell phones.

Maui’s emergency services chief, who made the decision not to activate sirens used for tsunami alerts, defended his action then resigned.

How will our leaders provide critical information?

Norton wants to bring back the alarm system, which could signal one or two beeps for tsunami or wildfire.

Water

On Maui, firefighters said the water pressure was feeble — not enough to fight the blaze — so they focused on evacuations.

Land that was in plantations of pineapple and sugar cane has been turned into mansions, luxury resorts and golf courses, with fish ponds disappearing to create hotel parking lots.

How vulnerable are we?

So much of the water in Santa Cruz County is used to grow berries and lettuce.

We have just one reservoir, Loch Lomond in San Lorenzo Valley.

What is our game plan if we need more water for firefighting?

Power

Hawaiian Electric, which provides power to Maui, did not shut off the power before high winds hit, as PG&E has done locally — and Hawaiian Electric is now facing lawsuits claiming it should have de-energized power lines due to the hurricane winds.

What about in Santa Cruz County?

If the electricity is shut off, are the water systems backed up by diesel generators?

Are the pipes at risk of rupturing from a wildfire’s intense heat?

In 2020, because of the CZU Lightning Fire, the San Lorenzo Valley Water District incurred $27.8 million in damages to water lines and tanks.

On Aug. 19, Michael Zwerling’s KSCO 1080 AM radio – that’s right, he opted not to sell or retire — lost power and its backup generator failed. The radio station, which has been a lifeline in past emergencies, now has phones relying on internet, so it was knocked off the air for two days.

What if this happened during the next wildfire? Does the backup system need a backup?

Could ham radio operators help?

In June, this newspaper wrote about ham radio enthusiast John Gerhardt of Soquel, who is the district emergency coordinator of the Amateur Radio Emergency Service in Santa Cruz. Can his team fill the gaps?

Escape Routes

Lahaina has one main street, Front Street, that runs by the ocean. There is a bypass road, which was closed Aug. 8 due to wildfire flareup in the hills. It reopened a week later.

Hurricane winds toppled 30 trees in West Maui. Roads were barricaded because of downed power lines.

That pushed everyone trying to escape onto Front Street — too many cars on a two-lane road with flames overtaking them, which is why you see photos of abandoned burnt out cars. With no way out, people jumped into the ocean. Some survived, others drowned waiting for help that never came.

San Lorenzo Valley has one main street, the winding Highway 9 through forests. If that’s closed, fleeing a wildfire will be difficult.

And what if Highway 1 were closed? What then?

Hawaiian Electric did a study after the 2019 Maui wildfires that concluded much more needed to be done to prevent power lines from emitting sparks. Since then, how much did Hawaiian Electric spend on wildfire projects on Maui: From 2017 to 2022, less than $245,000. Clearly not enough.

On Aug. 24, Maui County sued Hawaiian Electric, alleging negligence, saying the utility should have shut off power lines in response to the National Weather Service “red flag warning.”

The Legislature also played a role.

In 2015, lawmakers mandated that 100% of Hawaiian electricity come from renewable sources by 2045, a first for the U.S.

In 2017, Hawaiian Electric said it would reach the goal five years in 2040.

Did that focus — mandated by lawmakers — mean less attention to wildfire projects?

In California, even on my street in Scotts Valley, I see overgrown trees very close to power lines. Are other priorities diverting attention from Pacific Gas & Electric wildfire safety projects?

The Missing

In Maui, two weeks after the fire began in Lahaina, Hawaii’s one-time capital, officials do not know how many lives were lost. They say 115 died, but 800 to 1,100 are unaccounted for.

Local officials have not released a list of the missing due to privacy concerns and worries about traumatizing families. Maui Police Chief John Pelletier also serves as coroner. The island, which typically has 220-240 deaths a year to investigate, has no medical examiner. Now the FBI is working on a list, and set up a hotline — (808) 566-4300 — for relatives of the missing to call.

A man who works for a Maui funeral home posted what it’s like to pick up dead bodies. These people were incinerated. There are no clues as to who they are. This is why officials are asking families to provide DNA samples to help identify remains. However, few have done so.

The lack of information prompted Ellie Erickson, 27, of Kihei, to create a spreadsheet to track the missing. She has 8,000 followers on Instagram.

The Maui Police Department told the medical examiner in Honolulu, where burn patients were being treated, not to release the names of anyone who died due to fire injuries in Lahaina. This came after one burn patient died and his name appeared in media reports after next of kin were notified.

Let’s talk about privacy concerns and trauma worries — before the next disaster.

I’d like to see a report from the Santa Cruz County Emergency Management Council — which does not include any ag or water representatives as of now — to give us assurances that these questions have been considered and provide answers.

•••

Do you have more questions? Email me at info@cyber-times.com