By Deborah Osterberg

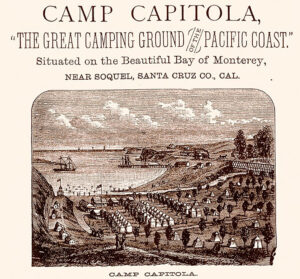

The main attraction of Capitola, its location along a picturesque shoreline, is also its Achilles heel. The lowlands are prone to flooding and the destructive power of high tides. Many of the initial, poorly constructed canvas tents and wooden cabins of Camp Capitola (1874), built near the shore, often suffered storm damage.

Capitola’s owner, Frederick Augustus Hihn, sought to expand and upgrade the beach resort into a more elegant tourist destination and locale for vacation homes. Unfortunately, he appeared to dismiss the dangers inherent in Capitola’s low-lying areas and continued to build upon them for the next couple of decades.

Starting in 1882, Hihn embarked upon an infrastructure upgrade starting with cutting and grading Monterey Avenue (then known as Bay Avenue). After a landslide the following winter, a retaining wall was constructed with fossilized rock from the area below “Lover’s Lane” (Grand Avenue).

Capitola Wharf damage, November 1913.The wharf was built in 1856. • Photo Courtesy of Capitola Historical Museum

Dirt fill taken from the cliff by tramcar, was spread over one and a half acres of creek flodplain and smoothed for new construction. Pilings were driven along the edge of Ocean Front Avenue for a boardwalk “to afford a charming stroll for day or evening.” Soquel Creek’s natural bed was shifted west to widen the beach and provide easier access.

Hihn then hired Edward L. Van Cleeck to design a replacement for the original hotel. In 1895, Van Cleeck built a 160-room hotel (Hotel Capitola) at the base of Depot Hill.

Hihn also directed that six large houses (the Six Sisters) and a line of resort concessions be built along Ocean Front Avenue.

It was only a matter of time until the sea swept back in to challenge the new man-made landscape.

On the morning of Nov. 26, 1913, a storm surge carried water up Capitola Avenue and over the tracks of the Union Traction Company streetcar line, presenting “a scene of wild desolation.”

Camp Capitola advertisement: Built in 1874, the wooden cabins erected near the shore to attract vacationers often suffered storm damage. • Photo Courtesy of Capitola Historical Museum

Realizing the potential damage to his boats, fisherman Alberto Gibelli hurried out to the wharf. As he was securing his gear, the rough surf collapsed the midsection of the wharf deck about 20 feet from him.

Gibelli was stranded.

On shore Gibelli’s wife “… fell on her knees and called on heavenly aid to bring her husband relief.”

An initial attempt at rescue was made by local celebrity and member of the championship Boston Red Sox, Harry Hooper. The right fielder was unsuccessful at pitching a baseball tied with a rope out as far as the wharf.

Four hours later, G. Stagnero, a fishman of Santa Cruz, threw a fishline with a lead on it to the marooned man. He caught it and hauled it across and the larger rope attached to it, and a life preserver. He put on the life preserver and tied the rope under his arms.

Gibelli leapt into the ocean and a group of fishermen on the beach pulled him to safety. He resurfaced “as calm as a cucumber and the least ruffled of any one concerned in the crowd.”

Although efforts to clean the beach of pilings, logs, and other rubble took more than two months, the beach was spotless, and life was back to normal for the resort town when tourists flocked back that May.

In 1919, the new owner of the resort, Henry Allen Rispin, began demolishing Hihn’s old concessions along Ocean Front Avenue.

In architecture, Rispin favored the popular Spanish Colonial Revival style, using concrete and stucco. At his direction, architects George McCrea and Helen Benbow redesigned and curved the road along the shoreline, moving it closer to the sea.

They rebuilt concession buildings along what Rispin christened “the Esplanade.”

Van Cleeck’s bathhouse along Soquel Creek was replaced with a stucco building featuring three central arches.

On Feb. 12, 1926, the sea returned. A 20-foot surge battered the Esplanade, cutting into the foundations of the new Venetian Court Apartments and once again flooding Capitola Avenue.

The entire village was under from six to eighteen inches of water. Much of the Esplanade was destroyed, with damages estimated between $6,000 to $10,000.

At 9 a.m. the waves here were breaking over the top of the bathhouse and in one half an hour this (wooden) building was virtually destroyed.

The diving platform to the right of the bathhouse was also practically demolished, as was the shoot-the-chutes on the left of the main building. The big concession building, erected only last spring, lost practically all its underpinning and was sagging precariously …

And so, it continues, the one constant in Capitola’s history — the relentless cycle of storms and tides, destruction, struggle, and the subsequent determination to pick up, rebuild and carry on because we love this special, beautiful place and there is nowhere else in the world we’d rather call home.

•••

Deborah Osterberg is curator of the Capitola Historical Museum, which will reopen in March with a new exhibition, “Capitola: Signs of the Times.” Hours will be noon to 4 p.m. Friday-Sunday.

For research questions, email capitolamuseum@gmail.com