By Edita McQuary

“The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

Current Middle East events remind me of my family history of fleeing out of harm’s way 80 years ago.

In August, 1939, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Non-Aggression Agreement was signed between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union dividing northeastern Europe between themselves. The Soviet Union was to get the Baltic States (Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia), Belarus, Eastern Poland and Finland, while Nazi Germany was to get West and Central Poland.

Soon after this, the Lutheran pastors in Lithuania (and perhaps in the other affected countries) started to warn their parishioners who were generally of German ancestry to consider leaving southwestern Lithuania and emigrate to Germany.

Now who would want to emigrate to Nazi Germany, you ask? Many German-descent families had already suffered under the Soviets in World War I.

My grandfather and many other Lithuanian Lutherans spent years in Siberian prisons for allegedly being German partisans.

Grandfather Karl, in the late 1890s emigrated to the United States and worked in thePennsylvania coal mines for a number of years. Upon his return, he bought a 75-acre farm near Marijampole close to the German border. In 1903, he married Mathilda, a fellow Lutheran, and they raised a family.

At the beginning of World War I, they had three sons and two daughters and a successful farm when a neighbor accused him of being a German collaborator, which, of course, he was not. The Russian army took him, as well as many others of German descent, to Siberia to spend the war years working in mines and subsisting on little more than potato peelings.

At war’s end In 1917, he and others were released to go back to their families. Grandmother hardly recognized him – he was mostly skin and bones. Being young, however, he recuperated and he and grandmother had two more children, my aunt in 1919 and my mother in 1921. The older siblings used to call them the “two Russkies” because they were born after grandfather came back from Siberia.

At war’s end In 1917, he and others were released to go back to their families. Grandmother hardly recognized him – he was mostly skin and bones. Being young, however, he recuperated and he and grandmother had two more children, my aunt in 1919 and my mother in 1921. The older siblings used to call them the “two Russkies” because they were born after grandfather came back from Siberia.

Grandfather died of lung disease in 1936 in his early 60s — coal mines and Siberia killed him.

By February 1941, the Soviet Russians were already in Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital, and would soon be in southwestern Lithuania. Heeding the warnings of the pastors, grandmother Mathilda prepared to flee to Germany with her unmarried children: Two sons, two daughters — and my mother and father who had just married three weeks earlier so they could escape together.

Choosing to stay behind was the oldest daughter, Ona, her husband, Jonas, with their two young children. Grandfather had given them a good-sized farm as her marriage dowry and they did not want to leave this to the Russians.

Again, a neighbor accused them of being Nazi sympathizers and the husband was taken to Siberia. My aunt and the two children were transported to Tajikistan along with many other Lithuanian Lutherans.

She was forced to work on a cotton farm where there was very little food. Her two young children were put into a Soviet orphanage and grew up believing they were Russians. My aunt died at age 44 from starvation. Many other transported people also died.

Her husband, released from Siberia after the war, went back to Lithuania looking for his wife and children. When told of their fate, he had a mental breakdown, became an alcoholic and also died young.

On Feb. 21, 1941, grandmother and her family hitched up the horses and drove a wagon out of Lithuania into Germany, out of the Soviet Army’s grasp. Bombs were dropping being dropped over northern Germany regularly.

The men were recruited (forced) to work in a mine in the Harz Mountains digging for minerals necessary for the war effort. After the mine gave out — there was no other work available except the German army. My uncles and father joined the army, were captured, and were not heard of for a very long time after the war ended.

Of course, these events, as bad as they were, pale in comparison to the slaughter of thousands of Lithuanian Jews in Lithuania by the Nazis with the complicity of the Lithuanian population. Fortunately, DNA testing was not known at that time. If it had been, my 2% Jewish DNA would have consigned me to the same fate.

We all know how this war ended. Thank God for the Americans who helped the Allies save Europe but at a great loss of American military lives. We are eternally grateful for their sacrifice!

After the war’s end, there was a choice for us displaced persons. We could stay in Germany and suffer the consequences of no shelter, no food, everything bombed out. Or, we could become refugees under the International Refugee Organization program of the United Nations and emigrate out of Germany. Between 1948 and 1952, 36,000 Lithuanians emigrated to the United States.

Many more thousands, perhaps millions, of displaced Europeans emigrated to the U.S., Canada, Australia, Great Britain and South America.

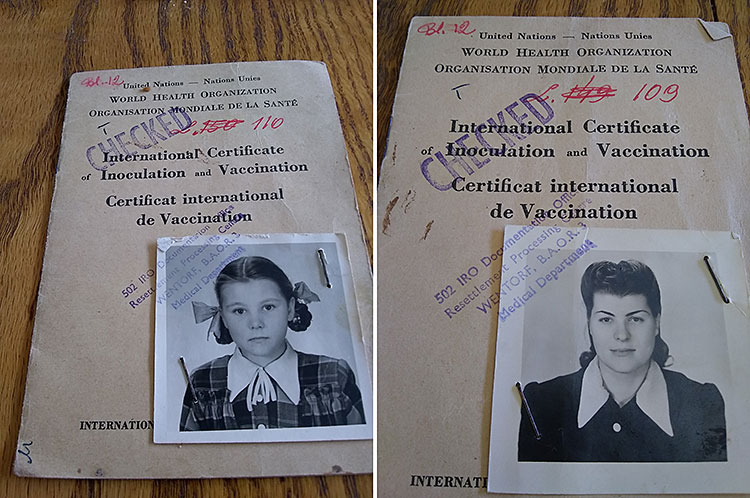

For about two months we stayed in the Displaced Persons relocation camp barracks and were carefully vetted to be sure we were not war criminals.

Then we had medical examinations every week. One week it was eyes, another week it was ears, then other parts of the body, and immunizations.

During one of these examinations, it was discovered that our mother had nasal polyps. They operated to remove the polyps so she could be healthy to support herself and her two children.

All of this was paid for by the International Refugee Organization, of which the United States was the biggest contributor.

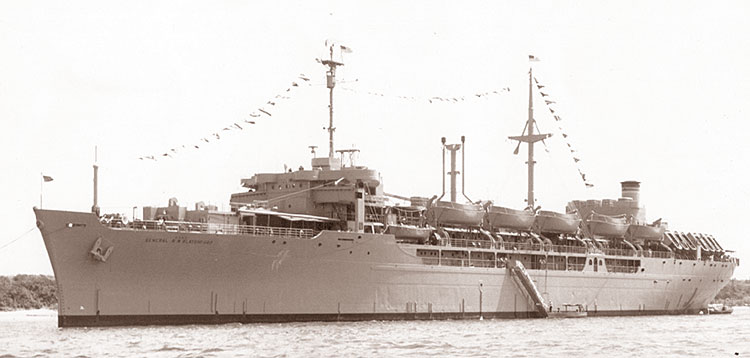

On March 31, 1951 after a scary but thrilling nine-day sea voyage on the U.S.S. General Blatchford, we landed on Ellis Island. Once on American soil, we were expected, with the help of our sponsors, to pay our own way.

We took a long train journey to Chicago where our sponsors lived. They had arrived in the U.S. a year or two before us and had agreed to shelter us, help Mom sign up for English classes, and take her to find work.

This Lithuanian married couple with two very young sons lived in a three-room basement apartment in Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood, one of the poorer parts of Chicago.

They naturally wanted to help Mom find work and get us our own apartment. In a month or so, Mom found a job and we were fortunate to rent our own two-room makeshift “apartment” built in the front of a garage.

I cannot say we were welcomed with open arms by the Irish-Americans in Bridgeport. We were not Catholic and we were competing for jobs. But, as we got to know each other and could speak English, we were accepted and became friendly neighbors.

Over time, as we immigrant families improved our English and got better jobs, we were able to move into better places and to live in better neighborhoods. Our version of upward mobility.

In those years, from after the war to perhaps early ‘60s, every immigrant had to fill out an address form each January and submit it to the government. The U.S. government wanted to know where we were living in case they needed to contact us. We never questioned this process and did not feel it violated our right to privacy. We were just thankful to be in the United States.

So that was Immigration Old School. I am not saying it was a perfect system but it certainly worked for so many of us who arrived here in the U.S. after World War II. And, in spite of difficulties and setbacks, we all learned the language, became citizens, paid our taxes, educated our children, and wound up living good lives in this great land of opportunity!

God bless America!