By Jondi Gumz

In 1954, Santa Cruz County voters were not inclined to support tax measures for education — even though all high school graduates had to leave the county to pursue a bachelor’s degree. When a bond measure to create a junior college went to voters, 70 percent said no.

So how did Santa Cruz County get a community college? Why is that college named for navigator Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, a name today’s faculty and students find objectionable because of his activities in the new world? Who vetted the name?

Sandy Lydon, who taught history at Cabrillo for more than 40 years, recounted what happened for the college’s Name Exploration Committee on April 15, a talk that is recorded on YouTube.com.

“This was a higher education desert,” he said.

Here is the history he shared:

In 1948, with World War II over, the U.S. military had surplus bases, such as Camp McQuaid on San Andreas Road in Aptos. Elsewhere, those bases were being converted to junior colleges.

Education superintendent Thomas MacQuiddy, enthusiastic about a 400-acre oceanfront property available for one dollar, formed a coalition from the three high schools in Boulder Creek, Santa Cruz and Watsonville to support the idea.

The state objected because the site wasn’t near a transportation corridor. And the county Board of Supervisors voted 5-0 against it, due to concerns about taxes.

Monterey Bay Academy, a private prep school, got the property.

The county was split because people in the north and south had different interests.

Watsonville was an agricultural town with farms and ranches. About 200 high school grads a year went to Hartnell College in Salinas.

Santa Cruz was a manufacturing area, the Wrigley plant was the new place to work, and city leaders wanted to attract a University of California campus, but without a junior college, that would be difficult.

So, they rallied support for a junior college bond measure in 1958, winning with a 66 percent yes vote.

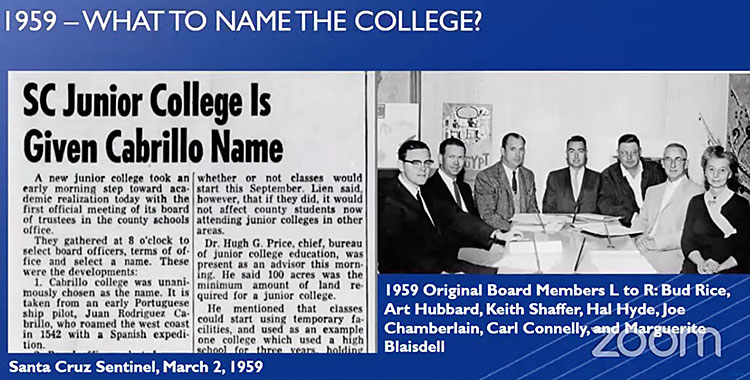

A slide from Sandy Lydon’s presentation about the naming of Cabrillo College, featuring the original Governing Board.

There were two very important conditions: The name of this junior college had to be neutral — nothing to do with Pajaro Valley, nothing to do with Santa Cruz — and the location had to be midway between Santa Cruz and Watsonville.

The vote came on the heels of Legislature in 1957 declaring Highway 1 to be “Cabrillo Highway.”

Signs reminded locals of this.

As the first European navigator to make landfall in San Diego, Cabrillo was “a southern California guy,” Lydon said. “They had no clue up here at the time who he might have been … if the Legislature had vetted him.”

At the time, Cabrillo was embraced by the Portuguese community for his navigation heroics. Information confirming his Spanish heritage had not come to light.

Wally Trabing, then a reporter with the Santa Cruz Sentinel, listed possible names for the junior college at the end of one article: Cabrillo, Begonia, Loma Prieta, MidCounty and Santa Cruz County.

After that, “he planted the name Cabrillo in various articles with quotes around it,” said Lydon, who interviewed six of the original trustees, plus administrators and students. “It had no official name.”

According to a report in the Sentinel on March 2, 1959, the name Cabrillo was chosen unanimously by the trustees Carl Conelly, Albert “Bud” Rice, Keith Shaffer, Margaret Blaisdell, Harold Hyde, Joe Chamberlain and Arthur Hubbard. (Conelly was active in San Lorenzo Valley, Chamberlain was a cattle rancher, Hubbard was a computer guy working at the new Lockheed Martin plant.)

Two days later, Frank Orr, editor of the Register-Pajaronian, wrote an editorial, “A Fitting Name.”

To start classes in September — a short six months away — the first president, Bob Swenson discovered vacant building at Watsonville High School available because it didn’t meet earthquake safety standards.

Cabrillo College opened with 400 freshmen in September 1959.

Next year, in 1960, bond measure $6.6 million bond measure, the largest in county history, was approved by 80% of the voters.

“The percentage vote was astonishing for a county that couldn’t hardly agree on anything ever,” Lydon said.

Cabrillo Civic Club of Santa Cruz, a group celebrating Portuguese heritage, commissioned a sculpture of Cabrillo that arrived in time for the 1966 graduation.

The figure is bearded, a serious look in his eyes, with Cabrilho — the Portuguese version of his name — on his belt. The sculpture and plaque are on campus in the Swenson Library but didn’t get much attention, as Lydon recalls.

Matt Wetstein, Cabrillo’s president/superintendent, asked why not choose Loma Prieta as the name?

It means “Dark Mountain” and it’s in Santa Clara County, Lydon said.

As far as changing the name, Lydon said, “It’s perfectly appropriate to ask him to come down and re-audition.”

He added that the people who chose the name Cabrillo “didn’t know who he was in 1959, in fact, historians didn’t know who he was … Harry Kelsey’s book in the 80s, we’ve learned more, absolutely.”

Lydon, who has written two books on immigration of the Chinese and Japanese to the West Coast, told of his visit to Tiananmen Square, where protesters were massacred in 1989. He wondered why Mao Zedong, a Marxist who freed China from colonialism then persecuted thousands, still has his name on buildings.

The answer he got: Mao was 80 percent not so good but 20 percent good, and people in China understand that.

As for the anti-Asian violence taking place throughout the country, Lydon said that is a part of Santa Cruz Country history, too, a story he shares in his book, “Chinese Gold.”

•••

To view Sandy Lydon’s talk, see: www.youtube.com/watch?v=GdqEVeeGI_w