By Jondi Gumz

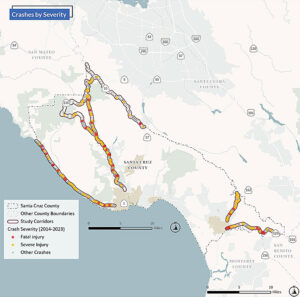

What can be done to reduce fatal crashes (and severe injury crashes) on our highways?

Specifically, Highway 1 north of Santa Cruz, Highway 9, Highway 236, and Highway 35 and Highways 129 and 152 outside the Watsonville city limits.

This does not include local streets such as Trout Gulch Road in Aptos near Trout Gulch Crossing, where local residents have called for safety measures because of cars hitting people on foot.

Overall crashes on these six highways dropped during the pandemic but have risen to near the 2017 peak. Since 2014, fatal and severe injury crashes have hovered between 20 and 30.

The Santa Cruz County Regional Transportation Commission has a Caltrans planning grant to identify locations of crashes and patterns of occurrence to generate and prioritize measures to create a roadmap to Vision Zero – Zero highway crashes.

The intent is to achieve zero traffic deaths and serious injuries by 2050 with projects and strategies implemented through close partnerships with Caltrans.

What Works Elsewhere

New York City, the first U.S. city to adopt Vision Zero in 2014, saw a 29% decrease in pedestrian deaths over a decade, as pedestrian deaths increased 67.4% nationally. New York City reprogrammed traffic signals to give pedestrians a few more seconds to cross, lowered the speed limit to 25 mph and installed automated speed cameras in school zones.

Hoboken, New Jersey, and Alexandria, Virginia, achieved zero traffic fatalities.

Hoboken removed parking spaces near corners to improve sight lines for motorists.

Alexandria adopted speed cameras for enforcement and created slow zones near schools and senior centers, painting the speed limit on the road for greater visibility. The city crowdsourced with the pubic to identify the most dangerous locations.

Survey Closes Dec. 6

The Santa Cruz County RTC is asking people to identify problem intersections, places you have witnessed crashes or near misses, or where you have safety concerns for those traveling using any mode of transportation. The survey closes Dec. 6.

About 20% of crashes result in a fatality or severe injuries.

When there is a fatality or serious injury, 11% of the time involves a person on a bicycle, 9% involves a person on foot.

A report prepared by planner Brianna Goodman presented data for consideration at a virtual public hearings on Oct. 23 and 24.

Highways 1, 129, and 152 all have around 35 crashes.

On Highway 236, a person on foot was involved in 68% of crashes and 11% a person on a bicycle.

Severe and fatal crashes increase on the weekend when more people are on the highways.

The most dangerous time for severe and fatal, crashes is 3-7 p.m. and from 7 p.m. overnight.

The fatal and severe injury accidents, improper turning was a factor more than 20% of time.

Unsafe speed and under the influence were each factors 20% of the time.

Are schools unsafe to walk to?

The report did not include data om crashes near schools.

To view the report see www.sccrtc.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/20241024-RHSP-M1-Slide-Deck.pdf

The timetable calls for strategies for safety to be developed by May 2025 and to work on the plan from March to November 2025.

The team will prepare a draft report and finalize upon receiving comments from Caltrans, the RTC, stakeholders such as Metro bus service, San Lorenzo Valley Unified School District, Pajaro Valley Unified School District, UC Santa Cruz, first responders, business groups, neighborhood groups and the public.

The final report, which will be presented to the RTC for input and approval, must provide a federally acceptable document for projects to compete and meet the requirements for Highway Safety Improvement Program and Safe Streets for All funding.